-

An IP lawyer talks about role-playing and copyrights—Saturday, November 9th, 2019

An IP lawyer talks about role-playing and copyrights—Saturday, November 9th, 2019

-

“WotC has a history of taking advantage of gamers’ ignorance of contract and intellectual property law and lack of wealth when making similar demands, thus harming the gaming community and industry, so it’s time those issues are addressed.”

It’s been a long time since I wrote my series on gaming copyright and why, and what kind of, open source licenses are useful and what are merely backdoor attempts to bar people from doing what they’re legally entitled to do under copyright law. As I stated regularly, I am not a lawyer, just an interested amateur. Frylock, as his name might suggest to you if you’re up on your Shakespeare, is a lawyer. He’s just started a series on copyrightability in RPGs, specifically stat blocks, at Frylock’s Gaming & Geekery.

His inspiration is very similar to my initial inspiration for writing Gods & Monsters: a threat from Wizards of the Coast. His came directly, however; mine only came obliquely through Ryan Dancey on Usenet. Keep an eye on his series—the first installment is very informative—and keep an eye on whether there’s a legal battle at all, or WotC/Hasbro just ignores him.

Robert E. Bodine: Part 1: Copyrightability of RPG Stat Blocks at Frylock’s Gaming & Geekery (#)

-

Combining damage dice into attack roll—Wednesday, April 18th, 2018

Combining damage dice into attack roll—Wednesday, April 18th, 2018

-

In Gods & Monsters, as in many role-playing games, the damage roll is completely separate from the attack roll. Dungeons and Dragons, historically, has had the same behavior: rolling a 20 is the same as rolling a 10, as long as both hit, with the caveat that a 1 always misses. The current edition, fifth edition, mixes things up a little by offering critical hits on a roll of 20, but a roll of 19 is still the same as any other roll.

This clearly goes against the grain for some players. You can see it in their eyes when they make a great attack roll and then roll a one or two for damage.

Because of this, I have occasionally considered making the damage roll somehow part of the attack roll, so that high attack rolls do more damage than low ones. The sticking point has always been that I’ve always thought about it in terms of the quality of the success, which would make such a rule more complex than it’s worth. It would also make it very difficult to damage opponents that were very difficult to hit, since the quality of success against an opponent that requires a 20 to hit, for example, will always be the minimum.

It occurred to me, though, that just using the raw attack roll wouldn’t be a big deal. While it’s true that, if you have to roll a 20 to hit and you’re doing, say, d8 damage, this would mean that you always do 8 points instead of 4.5, the real increase is from an average of .225 points per attack to .4 points per attack, since you’re almost never hitting anyway. Sure, it’s a big increase percentage-wise, but it really isn’t that big of an increase.

Using the raw attack roll makes the calculations much easier. There’s no adjustment for “how much did you make it by”. It removes agility, strength, and any situational modifiers from affecting damage unless you want them to, in which case just add it to the final damage.

Here’s how the common damage rolls in Gods & Monsters turn out in such a system:

-

The Great Falling War, Revisited—Tuesday, February 6th, 2018

The Great Falling War, Revisited—Tuesday, February 6th, 2018

-

“Whatever happens, I’ll send the results to Dragon Magazine!”

Delta’s D&D Hotspot claims to focus on “Math, History, and Design of Old-School D&D”, so it isn’t surprising that Delta has revisited the great falling war of 1983-84.

What is surprising is the data that Delta provides. After a lengthy analysis of the participants in the war, Delta adds:

The real-world statistics of falling mortality are expressed in terms of “median lethal distance” (LD50), that is, the distance at which a fall will kill 50% of victims (who are presumably normal adults). Smith, Trauma Anesthesia, p. 3, asserts that LD50 is around 50 feet (4 stories). Wikipedia asserts that LD50 for children is at a similar height; 40-50 feet. Dickinson, et. al., in “Falls From Height: Injury and Mortality” (Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 2013) notes that LD50 varies greatly by injury type: about [34 feet] for those who land on their head or chest; about [73 feet] for those who do not.

Fifty feet is a long way, and I don’t think I would have ever guessed that the mortality rate was only 50% falling that distance. Asked to guess, I’d probably have said 75% to 85% at least. This may be yet another case where real life is allowed to be stranger than fiction. Even more amazing is how much of a difference knowing how to fall makes: raising the LD50 to seventy feet just by falling better sounds like movie reality.

Of course, even not dying there’s likely to be a lot of injuries involved—although seeing the LD50 numbers does make me wonder what the serious injury rate is, and whether I’ve been overestimating that, too—and Gods & Monsters, unlike OD&D has a system for that. As Leland J. Tankersley writes in the comments,

I think the fundamental problem in reconciling reality with D&D-like games is that health in D&D is in some respects binary—you are either dead or effectively so (0 hp or less), or else you are “fine” (1 or more hp, which might be “near-death” in some sense but which doesn’t impair your ability to act in any way. While LD50 may be 50' for a typical human, I feel confident in asserting without evidence that the vast majority of those that are NOT killed by a 50' fall are nevertheless incapacitated (broken/shattered legs, for example).

-

Say yes or use the magic 8-ball—Saturday, December 19th, 2015

Say yes or use the magic 8-ball—Saturday, December 19th, 2015

-

The RPGPundit, in his own matchless manner as “the new and improved defender of RPGs” has taken on the utility of say yes or roll the dice. It’s something that has mostly gone unquestioned, even on (he would of course say especially on) the Forge. I used to hang out on the Forge a lot when it existed, and had many great conversations there.

Gods & Monsters uses a lot of of what I learned there, which is mainly that rules must mean something; if a rule doesn’t mean anything, get rid of that rule. You might think that this rule goes without saying, but having cut my teeth on AD&D in the hybrid form that consisted of some AD&D books, some Blue books, and some BX books, rules that didn’t mean anything or were never used are a basic part of my education.

Go through the amazingly cool AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, and most of those rules were not used by the writers, let alone by the customers.

From the Forge, I learned about hooks, but used them solely to help the game master end arguments about whether or not your character will do that. You said your character will do that, it’s right there on your character sheet. It is meant to divert play away from pointless, fun-sucking tedium.

It was there that I also learned about building your character in play, but the sole reason for building your character in play is to avoid skills that wouldn’t make sense in the pre-existing world.

But while “say yes or roll the dice” sounded very cool the first time I read it, you will not find it in the Gods & Monsters rulebook or in the Adventure Guide’s Handbook. The reason is that while it does sound cool at first glance, it has no practical use in the kind of games I enjoy playing in and running.

I enjoy games in which there is a world that can be interacted with, and through that interaction discovered.

That’s very different from the mindset of “say yes”, in which there is no such world: the world isn’t so much to be discovered as it is gamed. I enjoy the hell out of Donjon, but I wouldn’t want to play it long-term. And it knows this; Donjon is presented as an inherently silly game, much like Creeks & Crawdads but with a little more heft.1

-

The Biblical and other engravings of Gustave Doré—Saturday, July 25th, 2015

The Biblical and other engravings of Gustave Doré—Saturday, July 25th, 2015

-

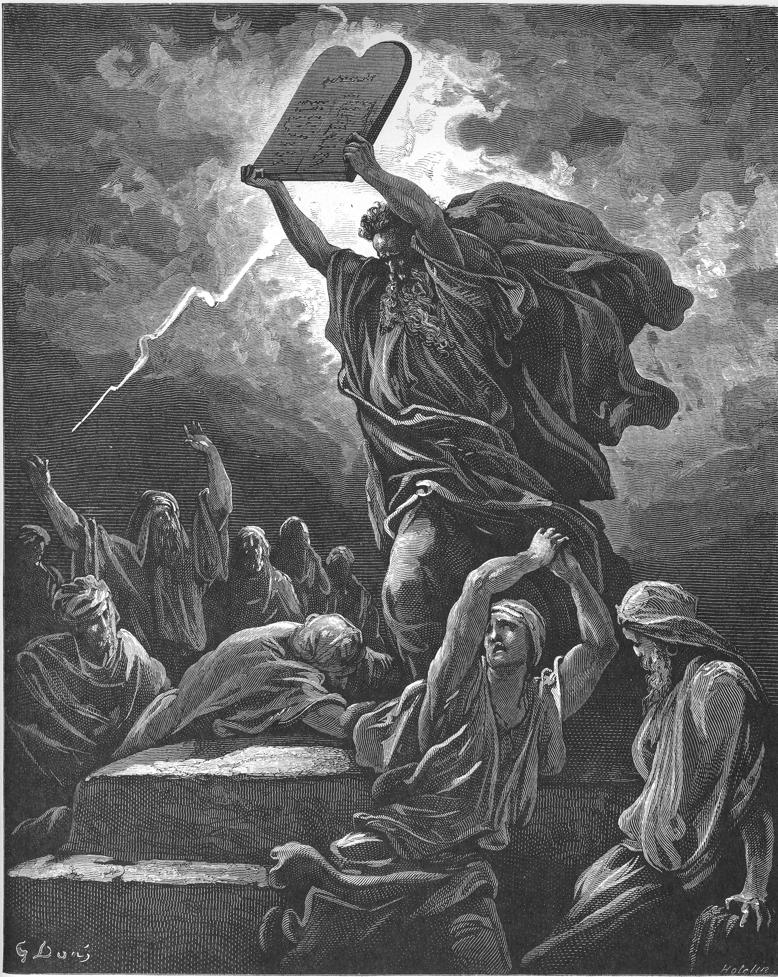

I haven’t used Gustave Doré as much as, say, Caspar David Friedrich or John William Waterhouse, but when I use him, I really use him. Moses Breaks the Tables of the Law appears twice in Divine Lore as well as in The Road, where the tablets of the law are one of the nine tablets of Enki.

I also used Jacob wrestling with the Angel in the main rulebook.

Part of the problem is that, as woodcuts go, his are not as evocative (to me, anyway) as William Miller’s. This may be simply because the reproductions available online aren’t as high quality as the reproductions of Miller that are available. Take a look at the best version of his work on The Raven, and there’s some really good stuff there—at fairly low resolutions. I’d love to use his Angels departing with Lenore into the sky, but the quality of the image just isn’t there.

Browsing through his works for “most gaming/fantasy-like art”, Bohemund alone mounts the rampart of Antioch is something I might use eventually, and Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise has potential, with its sword-wielding angel at the edge of the wood pointing the way to an angry Adam and tearful Eve.

-

The Pre-Raphaelite fantasies of John William Waterhouse—Saturday, July 11th, 2015

The Pre-Raphaelite fantasies of John William Waterhouse—Saturday, July 11th, 2015

-

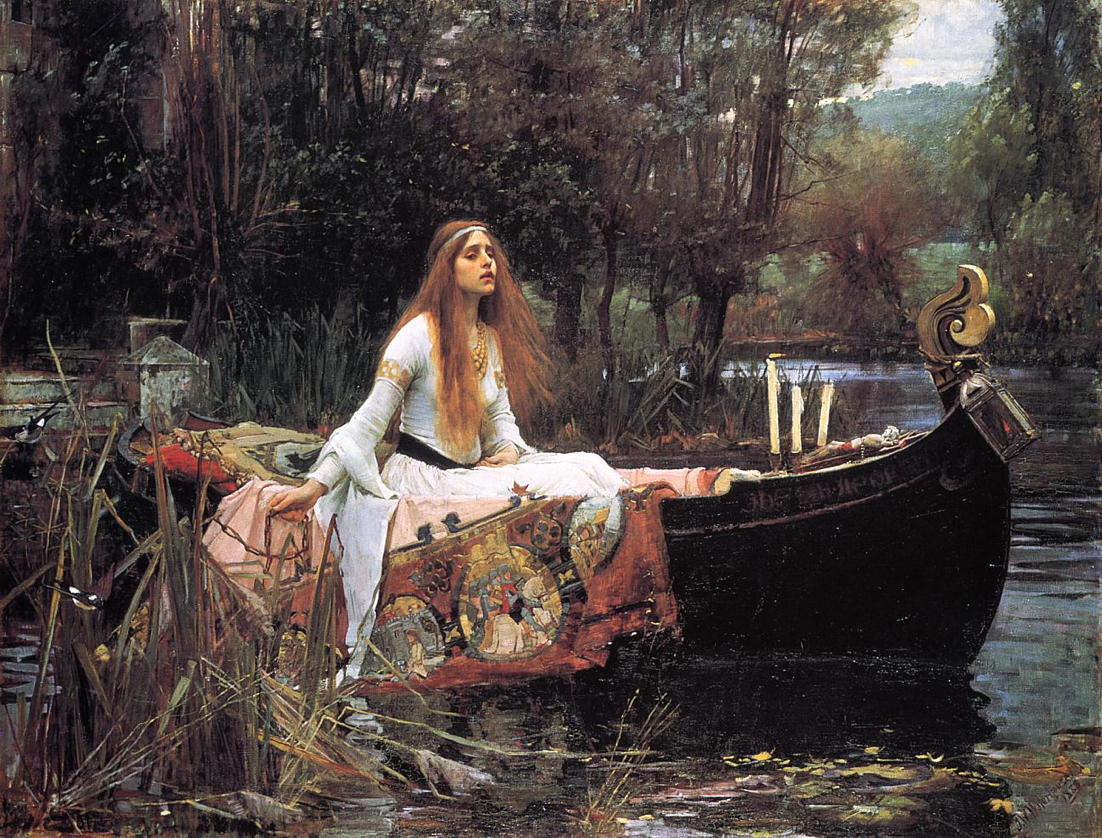

The Pre-Raphaelite movement is a gold mine for amazing fantasy artwork. Among the best was English painter John William Waterhouse. I use his work extensively in the Adventure Guide’s Handbook, and while I didn’t use the actual painting (yet), his The Lady of Shalott was the reason I used that poem in The House of Lisport. It’s just such an amazing piece of fantasy, the magical or fairy lady with knight-encrusted blankets and three candles lighting her waybill a prone crucifix… in fact it’s so amazing I just took out Waterhouse’s also-amazing Circe Invidiosa and replaced it with the Lady.

He created great paintings of rituals, from Circe Invidiosa with her preparing to turn Scylla into a hideous monster, to his Danaides pouring from three vases into a water-bearded cauldron, to, the most amazing in my view, his Magic Circle which is, precisely, a fantasy ritual, with burning incense, a magic staff, a magic circle, and a moon-shaped sickle. The sorceress has even attracted some ravens or crows to assist her!

Another favorite of mine is The Tempest, with the daughter of the sorceror Prospero sitting on the shoreline in a storm, watching what looks to be yet another ship dashed against the rocks by wind and wave. She’s worried mostly about her hair. I know that’s not the way the Shakespeare play goes, but it certainly looks that way in the painting.

-

Ethereal engravings of William Miller—Saturday, June 27th, 2015

Ethereal engravings of William Miller—Saturday, June 27th, 2015

-

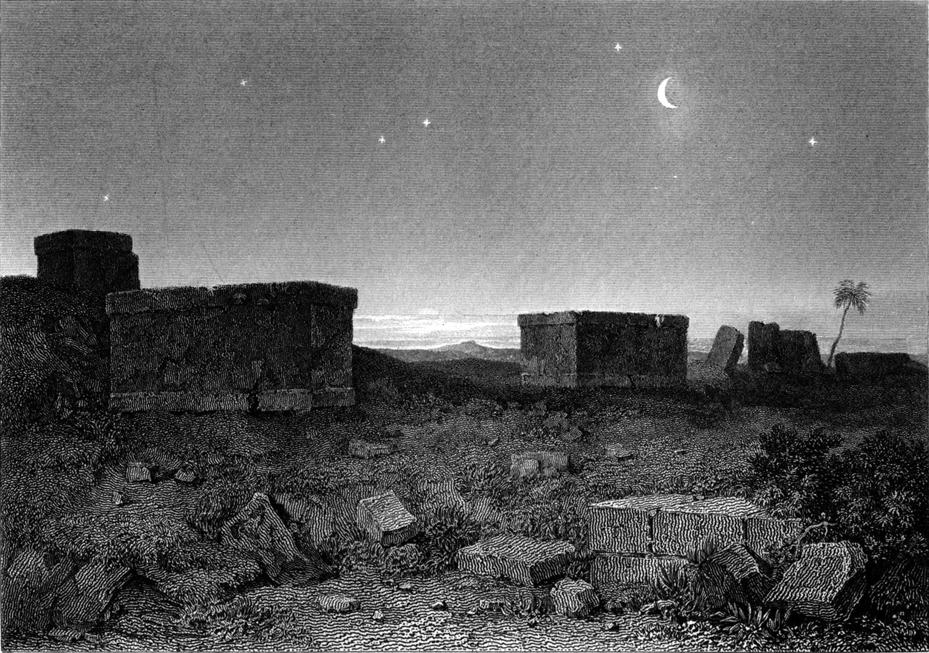

William Miller was a Scottish engraver. His artwork was created to accompany other people’s writings, and, as often as not, from the drawings of other people as well. This amazing image of Lochnaw Castle is from the Memoirs of Sir Andrew Agnew, by Thomas M’Crie. The engraving was from a drawing by R. K. Greville.

The Temple of Minerva and the Ancient Sarcophagi are from Select Views In Greece With Classical Illustrations, by Hugh William Williams, who also did the drawings that the engravings were based on.

His engraving of W. Linton’s drawing of Delos could just as well be Tolkien’s Last Home of the Elves. His Faeries on the Seashore (after W. Danby) is otherworldly—helped along, no doubt, by the fact that it’s an engraving, but the engraver’s skill and artistic talent show.

Engravings, while they reproduced other pieces of art, were difficult, time-consuming pieces of art themselves. Good plates could take years to engrave.

I have not yet used any of these images in adventures or lore books, but I can’t imaging that, at least, the Temple of Minerva or the Ancient Sarcophagi won’t inspire some use. The ancient sarcophagi look like something you might see in the cold waste on the Road to the First City of Man…

-

Inspirational art: Caspar David Friedrich—Saturday, May 30th, 2015

Inspirational art: Caspar David Friedrich—Saturday, May 30th, 2015

-

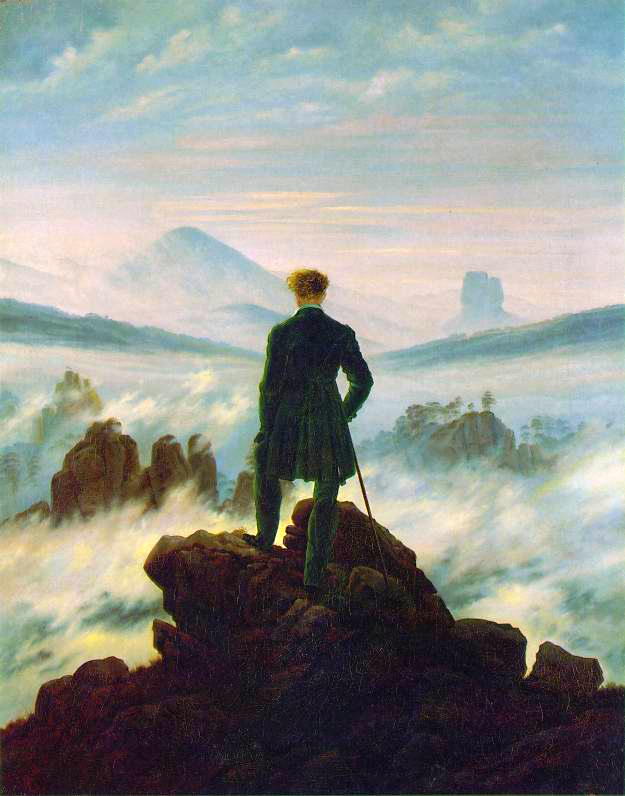

Inspirational art can really set the tone for a book or adventure. When I went looking for good fantasy art on Wikimedia Commons, the art of Caspar David Friedrich really stood out. His Wanderer in the Sea of Fog was so inspirational I used it as the first image in the Gods & Monsters rulebook: an adventurer, about to set off into the unknown, surveying the visible world before descending into the mist.

Other paintings I’ve used for various Gods & Monsters books are his Juno Temple, Cemetery Entrance, Monastery Ruins, Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, and, I think, the Abbey in the Oakwood. He has many more.

Two that really inspire me, though, are his Cross beside the Baltic and Man and woman contemplating the moon.

I strongly suspect that the cross partly inspired the cross in the snow in Song of Tranquility from Fight On! #7.

And doesn’t that tree look like it’s about to attack our contemplative moon-watchers?

Role-playing design notes

Random notes on the design of Gods & Monsters, and maybe even Men & Supermen if I can remember what I was drinking when I wrote it.