Spotlight on: Unaligned

In Dungeons & Dragons, there was a “neutral” alignment; there is no equivalent moral code in Gods & Monsters.

It is possible for a player to choose to be “unaligned” or “unaware”. These mean, respectively, that the character does not adhere to a moral code because they haven’t made that choice yet, or because they are unaware of any need to do so, respectively. At first level, most characters without a moral code are likely unaware.

Because being unaligned is not a halfway point between two poles as it is in D&D, Druids are not unaligned: “Prophets must have a moral code.”

What does it matter?

For purposes of the rules, there is no difference between unaligned and unaware.1 On a normal character sheet, the way to show that the character hasn’t chosen a moral code is to not write anything about moral codes down.

What are the practical effects of not having a moral code?

There are several spirit manifestations that operate according to moral codes; for example, protection from morality and ethical invisibility. These will have no effect on characters with no moral code. Other spirit manifestations, such as unravel spell and earth shot are more effective if the victim’s moral code opposes the prophet’s—there are penalties to the reaction roll, or bonuses to the prophet’s ability roll. If the victim has no moral code, these penalties/bonuses can never be applied to spirits manifesting against them.

Sounds like it might be nice to have no moral code!

But being without a moral code also makes characters more susceptible to some effects. The spirit manifestation divine service, for example, can’t affect targets that have an opposing moral code. An evil prophet can’t press a good character into divine service, nor can a good prophet press an evil target into divine service. But both can press an unaligned character into divine service.

And while no one can use ethical invisibility to hide from an unaligned character, neither can the unaligned character make use of ethical invisibility: the target must have a moral code.

There are also several specialties that are closed to characters without any moral code. A quick search shows that Charismatic, Exemplar, Long life, Nature friend, Poisoner, Power shift, Reliquary magic, and Seat of power all require a moral code of some kind.

What does unaligned mean in Gods & Monsters?

However strong or deep you choose to make them, moral codes are an important part of the game. They figure into spirits, archetypes, and specialties.

Even characters who are unaware that morality is the foundation of the world are still likely to have an intuitive understanding of the need for basic concepts of right and wrong. Their moral code is their answer to the very important question of what is right, and what is wrong.

To an unaligned character these things don’t matter much. If they had any strong opinion on the subject, their opinion would start to resemble a moral code. They would start answering the question of what’s right and what’s wrong. An unaligned character doesn’t think that it’s every man for himself in this dog-eat-dog world. They just don’t think about right and wrong at all.

Rush has famously sung “if you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice.” That’s not true in Gods & Monsters. When it comes to moral codes, making a choice means taking a moral stand, weak as it might be. A person who creates a system of ethics that says good and evil don’t matter is probably evil. The unaligned character doesn’t even ask the question.

In Gods & Monsters, moral codes are things of power. They exist. Whether they’re entities themselves, the foundation of the world, or the creations of the gods, moral codes are an integral part of the working of the world. As characters rise in level it will be hard to ignore this: spirits, specialties, and places of power will make it more and more obvious.

The person without a moral code doesn’t think in terms of good and evil, order or chaos. In Christianity, Adam and Eve were unaligned. They had no knowledge of right and wrong; within paradise, they had an easy life, and never had to make plans and choices for tomorrow. Everything was taken care of for them. With greater knowledge came greater choices. They began to realize that their action and their inaction had consequences. Before they came to recognize good and evil, their moral thought was like an animal’s. A lion and a deer are neither good nor evil; they’re just a lion and a deer.

A good example of the unaligned character that’s closer to home is the pure scholar; they care nothing for anything but their work, which they pursue with zeal. In Real Genius•, Chris Knight was unaligned. It would almost, but not quite, be reasonable to say that his religion was science. In fact, his religion was nothing: he pursued technical brilliance and left no thought for the greater choices a scientist must make. Chris Knight was neither good nor evil; he was just a scholar. He built lasers. That was it.

Hey, we’ve just built a laser that can cut through two cinderblocks, a wall, a statue, a tree, and still burn a burger sign! Ooh, burgers. I’m hungry. Let’s go eat and talk about lasers.

Even when he relaxed, he relaxed with lasers. He was a nice enough guy most of the time; he was an asshole some of the time. But he was never such a nice guy or such an asshole that it mattered. He lived from day to day, and any day that had lasers was a good one. Living as a student in the modern world, Knight never had to make any tough choices; he never had to make the choice between his work and the lives of others. Those choices were hidden from him, and he made no attempt to see them.

Such a character will have to undergo self-realization at some point, as Chris Knight did when, realizing that he’d been working for evil, he started “thinking of the immortal words of Socrates”. The unaligned character will eventually wonder what they just drank. Then they have to make a choice.

And at that point, not making a choice is a choice. Player characters need to choose something other than working for evil. Chris Knight could have chosen to continue working for people he knew were evil. Why not? He could play with some really cool lasers if he was willing to work for the shadow government of the movie. But he was one of the player characters, so he didn’t.

Oddly, the character Doctor Manhattan from the Watchmen• comic book was probably unaligned up to the point where he talked with Laurie on Mars. Despite being able to “see” the future and get a grand overview of time, he was little more than an obsessed scientist for most of the series.3 He focussed so much on the subatomic level that it never occurred to him that the human level had any meaning. But by the end of the series he had to see it, and once he saw it he had to make a choice.4

I’ve been talking about good and evil, mostly, because that’s easier. But unaligned applies to order and chaos, too. The unaligned character truly doesn’t think about how their actions affect the community or even necessarily how their actions affect themselves. They’re not selfish. They just don’t think that way. They’re just doing what they’re doing and getting through the day.

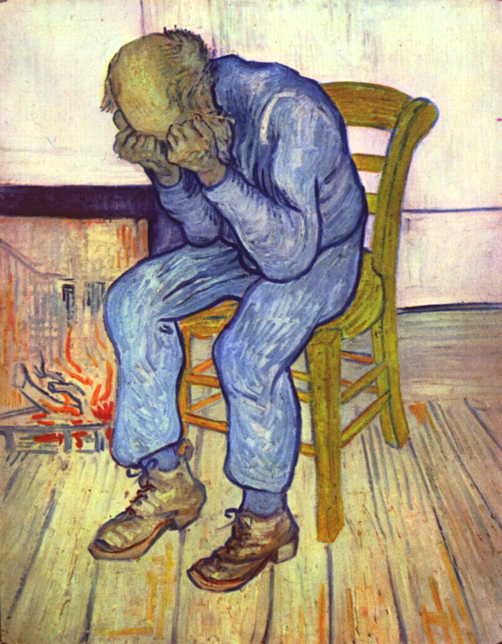

On the threshold of eternity, choices become clear—and difficult to make.

A crisis of conscience

A high-level character cannot remain unaware of the moral dimensions of the choices they make. If this sounds like the reason to be unaligned is to undergo a crisis of conscience during the game and then choose a moral code, well, I’m beginning to think so, too.

One of the things that Gods & Monsters has neither rules nor advice on is what happens when player characters don’t act their moral code. Gods & Monsters is not meant to be as adversarial as its predecessors. In the old AD&D books, dungeon masters were expected to plot character alignment on a chart and impose penalties when a character strayed into a different alignment. That’s never going to happen in Gods & Monsters. Players are expected to play their characters how they say they’re going to play their characters. If that’s no longer fun, they need to change what they say.

Players can change their character’s moral code; and unaligned characters can start paying attention to moral choices.5

A player character who chooses to become evil also becomes an NPC.

A prophet who changes moral code without the prompting of their deity or pantheon may not call spirits, or use any specialty for which “prophet” is a requirement. Their choices have cut themselves off from the divine.

For other characters, changing—or gaining—a moral code early in a character’s career isn’t going to be a big deal. In games where the divine powers take an active role in the world, however, the higher level a character is the more likely that such a change will not go unnoticed by whatever it is that moral codes represent. If the adventure guide already knows who is paying attention to the characters, then go with that. Otherwise, a good rule of thumb is for the adventure guide to make a d20 roll against the character’s level; adjust it for the nature of the game world and the nature of the character’s actions; and if it’s successful (if it’s less than or equal to the character’s level), there will be repercussions.

What kind of repercussions?

The best repercussions are chosen by the player/character. A character who realizes that they’ve been doing wrong should quest to right those wrongs. A character who fails to live up to their moral code, changes, and then changes back, should sacrifice to atone for their actions. What these quests and sacrifices should be need to be worked out in the game, but they should involve adventure for all of the player characters.

Adam and Eve had to leave paradise and build a new world. Chris Knight and his friends chose to make a shadow run on a secret U.S. science project. Doctor Manhattan left the game.6 In a fantasy game, the ways that a character will atone for past deeds will probably resemble the things that I wrote earlier about prophet adventures with, potentially, an act of sacrifice thrown in. They may need to restore some artifact, find some person who can right the kingdom, or save some homesteaders or a small village from marauders.

Often, their act of atonement will be the act that triggers their gaining a moral code. Whatever moral code they had before, if any, Katsushirō and Kikuchiyo in The Seven Samurai had made profound moral choices by the end of the movie.

In a world where moral codes are tangible things that can be seen by prophets, and where moral codes affect how the world acts on a character, being unaligned makes a player character a bit of an orphan; being unaligned is the domain of unimportant non-player characters. Heroes make choices; they act rather than let the world make choices for them. It’s easy enough to imagine a main character beginning the narrative with no discernible moral code; it’s difficult to imagine them reaching, say, tenth level without having made difficult moral choices.

I’ll probably drop the “unaware” term and just use unaligned. To be aware of moral codes but not to follow one is a moral choice in itself most of the time.

↑As far as I can tell, OD&D doesn’t define alignment. It simply gives the options of Law, Chaos, or Neutrality. Greyhawk has a short paragraph on Chaotic alignment, but that’s it. Gygax and co. were probably assuming that you’d read the fantasies that involved Law and Chaos. A lot of stuff went unexplained in those three books.

↑And in his flashbacks he just went along for the ride. He let everyone else make his decisions for him.

↑He had to make several choices in the end-game, not all of them good. But I don’t think he was a player character, he was probably a GMPC.

↑This was always meant to be true, but it was left up to each campaign. I’ve added a basic component of it to the rulebook, however: at each level advancement, the player and guide should consider if the character’s moral code has changed.

↑Arguably, he chose evil at the end, and became an NPC, if he was ever a PC to begin with.

↑

- Real Genius•

- A movie about college kids that didn’t dumb down college to get its laughs. One of my favorite movies.

- Rush—Freewill (Exit Stage Left): Rush

- Rush performing Freewill (live) from the Exit Stage Left show. Recorded in 1980.

- The Seven Samurai

- Probably the most influential samurai film, starring Toshirô Mifune and directed by Akira Kurosawa. It inspired more than just samurai: “The Magnificent Seven” was “Seven Samurai” remade into one of the most influential westerns.

- Spirit manifestations

- Search spirit manifestations, and make a list of all of the manifestations your prophet can use.

- Watchmen•: Alan Moore

- Destined to be one of the seminal works of the (modern or dying, take your pick) superhero comics industry. Moore weaves a tale of millennial fever in a world where the atomic bomb is big, blue, and looks like us.

More moral codes

- Spotlight on: Evil

- No one considers themselves Evil. So how does the Evil moral code relate to the game of Gods & Monsters? How and why do Evil non-player characters act?

More spotlight

- Spotlight on: The Saurian

- Who are these enigmatic lizards of ancient jungles? The saurian is the most unique of all the player character species.

- Mental mismatch

- High wisdom, low intelligence. D’uh, which way did he go, George? Which way did he go?

- Spotlight on: The Prophet

- Why would Mohammed, Jesus, or Moses head into a dungeon? A game with a prophet in a player-character role will be very different from a game without prophets. Something will need to drive Jonah into the whale.

- Spotlight on: Evil

- No one considers themselves Evil. So how does the Evil moral code relate to the game of Gods & Monsters? How and why do Evil non-player characters act?

- The ancient wizard

- What skills, specialties, and abilities are best suited for the stereotypical “ancient wizard”?

- One more page with the topic spotlight, and other related pages

This post was inspired by a post on Cave of Chaos, Gods and Monsters—Moral Codes.